Patricia E. Clawson

New Horizons: March 2015

Also in this issue

A Jazz Pianist Playing for the Glory of God

by Rebecca Sodergren

The Opera and Orchestral Music

by Alan D. Strange

Expressing One’s Faith as a Christian Artist

by Rebecca Sodergren

by Paul Browne

The hand of the Lord has been evident in Wael Farouk’s life from his childhood in Cairo to today as the first pianist ever to perform all ninety-eight of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s solo piano compositions within six months. That’s similar to an actor performing all of Shakespeare’s plays in one season, he says. What makes this achievement even more remarkable is that he was once told he could never play the Russian composer’s music because his hands could not be straightened or even made into a fist. Yet the thirty-three-year-old has performed in New York City’s Carnegie Hall. He also accompanies worship at his home church, Grace OPC in Hanover Park, Illinois.

Wael’s story begins as a two-and-a-half-year-old who couldn’t hold things in his hands in a normal way because of his shortened ligaments. To help strengthen Wael’s hands, a doctor urged his father to help him exercise his fingers. His father’s gift of a toy piano on his third birthday changed his life. Wael’s love of music was kindled as he continually played the piano.

Growing up in a Christian family in Cairo, Wael started to play in Coptic churches and even played before the Coptic Pope at four and a half. By eight, he played the first of many annual performances for Egypt’s then–First Lady Suzanne Mubarak.

Enrolling at the Cairo Conservatory at the precollege level when he was eight set the course of his life. Even though Wael scored the highest on the entrance exams, the school initially refused to admit him because of his physique, claiming it could hurt his psyche. Wael’s father, a hard-working man, negotiated a three-month trial in which his son would do the workload of two years in three months, which he did. Fourteen years later, Wael graduated with the educational equivalent of elementary school, high school, and college, scoring 100 out of 100 annually on his finals, which had never happened before.

Four years into his studies, he was appointed a Russian teacher for three years, who showed Wael how to be professional, dedicated, and hard working. At twelve, Wael was in a class of twenty-two-year-old graduate students who sometimes were left in tears by their teacher. But he worked hard, so it never happened to him. Wael got up at five, rode the bus ninety minutes to and from the conservatory, took classes from eight to five, studied his other subjects, and practiced at least six hours daily.

Wael’s father taught him his work ethic: “If there is something you really want, you have to give it everything.” When Wael’s father was nine, he and his older brother had to work two jobs to support their mother and four siblings. His father worked to put himself through college, often studying under a street light when there was no light at home.

One day Wael’s teacher gave him a recording of Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto. “It was like dropping a bomb on somebody’s head,” said Wael. “It was just too much—in a great way.” He told his teacher he would like to work on it. The teacher smiled and said, “A wise man knows his limits. I have worked on this piece all my life, but have not been good enough to play it.” The news shocked Wael since his teacher was very good. His teacher knew that Rachmaninoff was six feet, six inches tall, with large hands that spread more than an octave and a half. But Wael was only five feet tall, and his fingers barely stretched an octave. In the summer, Wael increased his practice time to thirteen hours a day or more. Two years later, he could play the piece.

Wael was scheduled to play the concerto with the Cairo Symphony, but the French conductor refused to let an eighteen-year-old play it in concert. However, if he played another piece well in concert, he would let Wael perform it the following season. His solo received multiple curtain calls. The next year, Wael played the Third Concerto, the first time it was performed in Egypt.

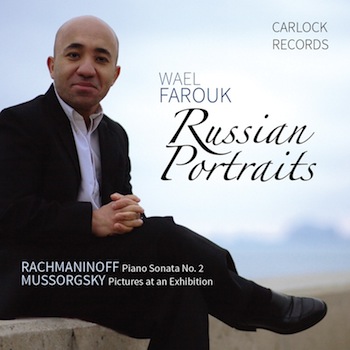

Over the years, Wael Farouk toured internationally, playing in England, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, and Russia, where he played Tchaikovsky’s own piano. He received seven full scholarships, including more than one Fulbright fellowship, to various schools. Hurricane Sandy canceled his first performance at Carnegie Hall, but he played there seven months later in 2013.

In 2014, Farouk accomplished what no other pianist has ever achieved. He performed all ninety-eight solo piano compositions of Rachmaninoff in five concerts within six months. While playing such a massive amount of complex music, he knew that he could make a mistake on any note.

Despite that renown, Farouk said his greatest accomplishment was marrying Amy Stahl, who grew up at Emmanuel OPC in Wilmington, Delaware. Farouk met his wife, then a senior English major, while earning his master’s at Converse College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. She invited Farouk to the Easter service at the PCA church she attended. Afterward they ate the first of many lunches with Chris and Susan Bennett. A PCA elder, Bennett taught him the Reformed faith, which Farouk often recognized as an articulation of his own beliefs. When he told his parents that he had joined a Presbyterian church, his father said, “You know, your grandparents were Presbyterians.” They had left the one Presbyterian church in Cairo after they moved, because they had no transportation to return there for worship.

Once engaged, Farouk studied in New York while his fiancée earned her master’s in Tallahassee, attending Calvary OPC. OP pastor William Hobbs performed their marriage ceremony. The Farouks then moved to Chicago, where he earned a degree and now teaches at Roosevelt University. He also travels to Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, to work on his doctorate.

The Farouks found a church home at Grace OPC, where he accompanies worship when he is available. As a child, Farouk learned stage presence from playing in the Coptic churches. Once, while playing for a service, he froze and couldn’t focus because people were eating while he played. Today in concert, Farouk may wait five minutes for the audience to become quiet.

It is different today when he plays the prelude before the worship service and people are chatting in the pews. “When I’m playing in church, it’s not really about me,” said Farouk. “It’s not really even about the pastor. We’re here to be in God’s house. We try to block everything out, not for the sake of music, but for the sake of hearing God’s Word.”

Grace OPC pastor Matthew Cotta said of Farouk, “His quiet, humble, thoughtful, and godly life has been a constant source of encouragement and edification to us all.”

“I believe really great music is God’s voice,” said Farouk. “Luther said music is only second to the gospel. All the psalms praise him with music skillfully. It’s not a career. It is something I am completely in love with, and it really takes over me.”

Farouk believes music has a spiritual aspect. There are no directions for the listener—just sounds—unlike watching a ballet where the dancer runs from the witch. The greatness of concert music is the way that the performer transmits the composer’s emotional context when he wrote the piece. Beethoven doesn’t describe his feelings when he wrote a piece, so the performer must learn about Beethoven, digest that information, and then creatively reflect it in the interpretation given to the music, Farouk said. The music then goes straight to the listeners’ heart and brain in a magical way.

“You are able to move somebody to tears without saying a word,” Farouk said. “If you’re doing it for God’s glory, then you’ll have the commitment and desire to do it all well.”

Farouk, who practices two to seven hours daily, hopes his newborn daughter, Nabiela Joy, will enjoy music because it will be in her blood.

“I want to be a good husband and father,” said Farouk. “On the professional level, I want to keep doing what I’m doing to the best of my ability. I’m very fortunate that I get to do what I love the most. It’s all for God’s glory.”

More information is available at www.waelfarouk.com.

The author is the editorial assistant for New Horizons. New Horizons, March 2015.

New Horizons: March 2015

Also in this issue

A Jazz Pianist Playing for the Glory of God

by Rebecca Sodergren

The Opera and Orchestral Music

by Alan D. Strange

Expressing One’s Faith as a Christian Artist

by Rebecca Sodergren

by Paul Browne

© 2025 The Orthodox Presbyterian Church